Creating The Discussion

Rationality, the quality of being based on or in accordance with reason, is one of the guiding values within contemporary Western thought (Neves, 2019). We often hear talk about making the ‘rational-choice’ or are encouraged to ‘think rationally’, yet little thought is given to what exactly this means. Nevertheless, it is in this blog that I will be exploring and unpacking this deeply embedded and taken-for-granted notion in an attempt to problematize it’s uncritical use not only for individuals but for Western society as a whole.

I will begin with the historical context; where exactly the idea of rationality came from, what it means and how it has become embedded in the very thinking and communicating of westerners, as well as the entire organization of Western society. Next, I will attempt to expose the deeper logic behind what rational-thinking means and entails, to further highlight some inherent issues involved in the process. Finally, to bring my argument full circle, I will highlight the broader consequences of modern rationality when it goes wrong, namely how it can lead to horrors as extreme as the Holocaust. In doing so and precisely because the notion of rationality is so deeply intertwined within Western thought, I hope to raise awareness of the dangers of its uncritical application, as well as, discuss further questions and implications for its use in the future.

Historical Contextualization

In order to fully understand what I mean when I speak of modern rationality, or ration-thinking, it may be useful to look into the historical origins of the notion.

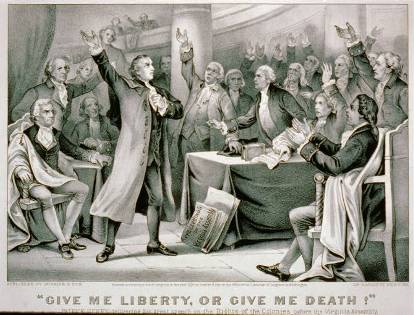

Born out of the humanistic spirit of the Renaissance era, rationality, as we will come to understand it in its contemporary context, is often traced back to the Enlightenment era during the 17th and 18th centuries in Europe. Alternatively referred to as an intellectual movement, this period was defined by a radical shift within the link between will, authority and reason (Foucault, 1984). It was the process whereby individuals, by using their freewill, broke away from the realm of obedience and authority, largely with reference to the strict religious authority of the time, toward the realm of reason (Foucault, 1984). Where previously, religious authorities had been relied upon for everyday decision making and social order, the shift toward reason emphasized the individual’s capacity to think, understand and form judgements for themselves by the process of logic (Foucault, 1984). People turned their focus to learning for its own sake, giving importance to human beings, rather than the divine or supernatural, to solve human problems in rational, reason-based, ways (Foucault, 1984). The Enlightenment became the ‘freedom of conscience’, the process whereby people participated collectively and autonomously, as an act of courage, to become more accomplished personally, by using reason as an end in itself (Foucault, 1984).

So what of rationality? It was during this period that the spirit of rationality began to form. Directly locating itself within the autonomous capacity of the human individual to reason for themselves, uninfluenced by religion or other dominating ideas, rational-thinking becomes the guiding ideology, aligning itself with truth. Here rationality, or ration-thinking, is intertwined with values of individualism and autonomy, the emphasis and reliance upon individuals to reason for themselves and govern their own lives; collective reasoning, the idea that autonomous individuals working together are able to make rational choices for social order of society; progress, the aspiration and eagerness for both individual and collective societal growth and finally; truth, the emphasis upon objective, uninfluenced and reliable outcomes of rational thinking.

Rational Modernity

Despite undergoing much change, the precise values born out of the Enlightenment, such as the idea of progress, individual reason, as well as the desire for mastery of knowledge and our world, have not only remained within the attitude of modernity, but have been accelerated (Neves, 2019).

Today, on the smaller-scale, a highly individualistic ideology has formed out of the emphasis upon reason and autonomy. It is generally understood that individuals are self-governing and responsible beings, who should form their own opinions without looking completely to authority for answers, should make their own decisions and are therefore masters of their own destiny (Neves, 2019).

On a larger scale, the value of progress, mastery and, once again, reason, have led to both the industrial and scientific revolution (Neves, 2019). From here we see the formation of capitalism and bureaucracy, both the institutionalized embodiments of rationality in its systematic, progress and efficiency oriented structure. Everything from the economy to politics, the judicial system to academia, public transit to daily planning, follow rationalized patterns.

Nevertheless, while abstract, the notion of rationality does not only encompass a reliance upon reason, but should be understood in its historical realization and the importance given to it, to highlight a certain capacity for reason among human beings and its ultimate goal of truth, efficiency and progress.

Rational Choice Theory/ The Logic Behind Rational Thinking and Decision-Making

Thus far I have tried to paint the picture for where the notion of rationality has come from, what it means and how it has manifested itself in modern Western society. However, to this point, precisely what rationality means, or what it rational-behaviour and thinking entails, remains unclear. Nevertheless, where the product of rational-thinking and decision-making is often made the point of evaluation, I would like to turn my focus to the process and logic whereby ration-choices are generated.

In the article, The Nuts and Bolts for the Social Sciences, Jon Elster skilfully captures three main criteria underlying rational choice and action within Rational Choice Theory (RCT). Following it’s argument, a rational choice must firstly, “be the best means of realizing a person’s desire, given his beliefs” (Elster 1989, 30). To clarify, for a decision to be rational, it must initially be in line with the beliefs and motivations of the individual, since acting out of line with these would be unreasonable (Elster, 1989). Next, “these beliefs must themselves be optimal, given the evidence available to them” (Elster 1989, 30). Here, we see and know that it is not enough to deem a choice rational without taking into consideration other possibilities. The decided line of action must be the one which comes as the most absolute, among all the other thought-out possible desires, and which will effectively result in the fulfillment of the optimal desire (Elster, 1989). Finally, “the person must collect an optimal amount of evidence – neither too much nor too little. That amount depends both on his desires – the importance he attaches to the decision – and his beliefs about the cost and benefits of gathering more information” (Elster 1989, 30).

If you recognize Rational-Choice Theory, or it seems to make sense intuitively, this is no coincidence. While often overlooked, the process and formation of rational decision-making which Elster is outlining is the very pattern and systematized way of decision making which is relied upon and deeply embedded within Western thought.

However, while perhaps initially tempting, RCT quickly becomes problematic when more critically assessed. According to RCT, in acting rationally, it is the individual in isolation, channeling their capacity of reason, who chooses what is best for themselves (Elster, 1989). Therefore, when facing multiple courses of action, the individual will consult their desires and beliefs to decide that which is superior to them, regardless of what other people might do or what the implications might be for them (Elster, 1989).

Immediately two problems arise here, the first concerning the notion of the isolated individual. RCT’s narrow view of individual decision making, an idea often perpetuated within Western society, does not take into consideration how people come to realize their desires and beliefs, nor how larger, powerful societal forces, such as the government, economic and political systems, religion or the media, work to influence and constrain their realization.

Secondly, what can further be seen is how desires are fundamentally both subjective and relative to each individual. This is problematic for the entire state of ‘rational-thinking’ because, as process which aims for a highly quantitative and logical quality, it’s roots ultimately lie in the highly unquantifiable, qualitative and complex elements which make up individual desires, such as their personal beliefs, feelings, emotions, and preferences within their individual life situations.

Additionally, perhaps most problematic of all, is the circularity of rational-thinking. As explicated by RCT, one not only begins the thought-process with their individual desires, but immediately deems them rational. Thus, if anyone wants to make a ‘rational argument’ for their choices and actions, their desires – whether rational or irrational to another person – are already valid (Elster, 1989). Going forward, and following the logic of rational-choice, the individual would next merely need to find enough evidence to prove their desires and course of action as optimal (Elster, 1989). This criteria surrounding sufficient evidence is especially unclear, with Elster even explaining that the amount of evidence depends on the desires of the individual, the importance they give to it as well as their perception of the costs and benefits of gathering more information (Elster 1989, 30). Nevertheless, it should not be hard to see how such logic easily becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy where by individuals may pick and choose what evidence to base their prefered decisions off, further making rational-choice merely a tool for the validation and pursuit of individual interests.

Nevertheless, whilst bearing the banner of ‘rationality’, a critical analysis of the patterned criteria underlying ‘rational’ decision-making not only problematizes its logic, but in the entire state of Western every-day thinking.

When Rationality Goes Wrong

Where I have tried to raise awareness by concentrating on some of the issues within the very logic of Western notions of rationality, it may be noted that, for the most part, these logical incongruities go unnoticed in the day-to-day decision making of individuals. This line of thinking does not necessarily cause problems when it is applied in grocery shopping or planning a commute to work, it is useful and natural, and when taken together – quickly makes up the entire organization and social order of Western society.

However, beyond the individual, I would like to show the broader implications and consequences of this way of thinking, when it goes wrong, on a larger scale by relying on Zygmunt Bauman’s analysis of the Holocaust.

According to Bauman, the horrific events of the Holocaust should not be referred to as an ‘out of the ordinary’ event, nor should it be categorized as another extreme, yet familiar, case of conflict, prejudice or aggression. When we consider the Holocaust in either of these ways it remains ‘unique’ but ordinary after all, and resists proper evaluation (Bauman, 1988).

For Bauman, a closer look at the Holocaust reveals its precise application of modern techniques to successfully murder millions of Jews, as well as other specific minority groups. The Holocaust was a highly rational, efficient and systematized occurence, drawn from modern bureaucracy models. Beginning with the star of David to identify Jews, not far or unusual to modern forms of documentation, to the efficient and quick transportation of its victims to death camps, and finally, the highly perfected and effective system for murder, which resulted in millions (Bauman, 1988). Each stage of the Holocaust was institutionalized and fulfilled the bureacratic criteria of rationality which characteristically put all the individuals involved at a distance, disconnected from the whole, and therefore, morally blind (Bauman, 1988).

Perhaps more interestingly, as Bauman points out, is the fact that everything about the Holocaust was normal in the sense of fully keeping up with everything we know about modern civilization. The Holocaust was always in line with modernity’s guiding spirit of rationality and priority of progress toward civilization, which apparently required the exclusion of certain groups (Bauman, 1988). As well, it followed proper modern pathways to pursue the desired outcomes, by rationalized and reasoned goals, which we know now can be easily done by anyone, especially when they have a lot of power (Bauman, 1988). This accounts for much of the reason why the Holocaust had continued for so long, or why so many normal individuals, who became Nazis, willingly participated (Bauman, 1988).

Moreover, it is significant that sociological analysis had hardly picked up on the fact that the Holocaust was a legitimate outcome of rational, bureaucratic and modern culture. Similar to the individuals involved in the Holocaust who were blinded by the guise of rationality, sociology too , developed and formed within modernity and its rational spirit, was rendered blind (Bauman, 1988). As a result, the Holocaust revealed a significant fault within the discipline itself, calling for dramatic revision and rethinking of it’s social theory and methods, which follow much of the same rational thinking and methods that made the Holocaust possible (Bauman, 1988).

Discussion

Nevertheless, in an attempt to raise some issues and awareness surrounding the all too common notion of rationality, I have tried to paint a picture. Where rationality, in its emergence during the Enlightenment, was a radical and positive shift for its time, we slowly see how its continued (over)use in modernity can bring about some problems. Yet, it has remained the same because, generally speaking, its results are positive ones. In the day to day lives of individuals, relying on rationality gets things done. Even in the case of important desires or plans, application of rational, calculated rules of efficiency really does bring upon progress for broader societal planning.

However, while rationality as having some positive outcomes where do we draw the line? Is it when it involves more than one person? Perhaps the Enlightenment did achieve something important, by putting reason and ability directly within the human individual themselves, instead of outside of them. Is it possible that this initial realization was the best that ‘rationality’ could do? Yet, rationality is deeply embedded within the comprehensive thinking and decision making among Western society. Perhaps, before completely discarding it, is there something that could be incorporated into rational-thinking so that it doesn’t go wrong?

Works Cited

Elster, Jon. Nuts and Bolts for the Social Sciences. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1989.

Neves, Katija. “The Enlightenment and Modernity” Class Lecture, Concordia, Montreal, Week 2, September 11, 2019.

What is Enlightenment? Interview with Foucault in Rabinow (P.), éd., The Foucault Reader, New York, Pantheon Books, 1984, pp. 32-50

Zygmunt, Bauman 1988 Sociology After The Holocaust The British Journal of Sociology, Vol. 39, No. 4, Pp. 469-497.